This is part of my memoir-in-progress. (Here is the First chapter)

When I first bought the house in Nevada City it was already kind of a crash pad, full of hippies and punks and their weed and drum kits and dogs and guitars. There were people renting rooms and people who just showed up and slept wherever they could—there was a guy who slept in a closet and another guy who snuck in every night to sleep on the living room couch, and another guy who slept on the other couch, the one on the deck, and downstairs there was Dino—so blazed out of his mind most of the time he was practically mute—who slept on an armchair at the end of the hallway. Another guy lived in a kind of makeshift shelter, right where the trees started at the edge of the meadow. I never saw him but I heard him sometimes, talking to himself. I wanted to keep renting out the rooms that were already rented, to help with the mortgage, but I also wanted to get rid of the extra people. I tried to a few times but it didn’t seem to take and I was kind of at a loss how to make it. I had talked to Dino, very reasonably I thought, and gently, and he agreed or pretended to agree to move out of his armchair and I thought it was all good but he was back in it again the next night. The house had been like this for a long time before I bought it and finally I decided it was easier just to accept it and not try too hard to change things right away.

Even with all the people coming and going the house was still pretty chill—it felt peaceful—and people were mostly respectful of one another and it was big enough, spread out over 3 stories, to stay fairly quiet. In the evenings it felt homey like a real house with a big family—always there but just out of sight, doing their own things. Eventually I became friends with my housemates. I especially liked hanging out with Julian, who rented a room right off the kitchen. Julian had freckles and long red hair and was completely obsessed with Otis Redding. I liked him and I liked Otis Redding and I loved his love for Otis Redding and never got tired of hearing That’s How Strong My Love Is or These Arms of Mine coming out of his room morning and night. But after a while it became clear that Julian was falling for me and the words of the songs started to have a new meaning, a loaded connotation, and hearing them made me want to cry. They normally made me want to cry anyhow, in a joyous, life-affirming way, but this was different. I had been in love with people who didn’t feel the same about me before but had never been on the receiving end; not from anyone who was sane or who I had to take seriously. I took Julian seriously though and didn’t know what to do. Before things got that way I had listened to Otis Redding with him and it occurred to me that maybe the reason some of his songs were so moving—almost maudlin but not quite—was because they were in 3, with that waltz-like quality that moved you or made you feel like moving whether you wanted to or not, and I started thinking that if a human heart beat in a lilting 1-2-3, 1-2-3 instead of a driving, incessant 1-2 beat we would probably feel pretty peaceful inside, we wouldn’t be violent, there wouldn’t be war, there wouldn’t be any strife or anything bad in the world and I said so because I could say shit like that to Julian and he didn’t laugh at me or if he did he followed it by saying “but you’re probably right.”

We stopped hanging out after I made it clear I was into someone else. It was very awkward because he was always there in his room right off the kitchen and we couldn’t really avoid each other. Finally he moved out and Jesse moved in. I was a little sad but couldn’t help feeling relieved that he was gone.

When Jesse moved in I kept my own bedroom upstairs and he set up his stuff in what had been Julian’s room. We spent a lot of time sitting on the floor listening to his records which quickly became our records because we were at thrift stores and yard sales every day buying all kind of records including old records from Greece and Lithuania and everywhere else and pretty soon we were learning songs from them on our violin and guitar. I hadn’t played my violin much since I’d left New York. Before that I’d been practicing hard, aware that if I did I might still get somewhere as a classical musician, but now, especially with this new kind of music, the pressure was off and I could have fun. I had played in a bluegrass band in college and before that in an Irish punk band, so I knew how to switch gears from playing like a soloist all the time—or at least how to lose some of the vibrato—but this was a whole new world of music to me and I was excited about it. We practiced all the time and eventually took it to the streets and then to the local music venues and radio stations. We played Ukrainian music and Greek music and Polish music and French music and Klezmer music. We played at the Old Timey Fiddler’s convention and won “best new band.” People listening liked the music because it was easy to like, and we loved playing it. I started to feel like my life and my future could still have music in it, that I could still be a violinist, even though I’d failed to become a famous soloist, failed to get a Sony recording deal like many of my peers. And Jesse—who was wholly without conceit or egoism, who never expected anything to come of his efforts, who had a normal amount of self-doubt and maybe then some—had so much energy, so many ideas, and was so intent on doing something with them, that we almost couldn’t fail.

Jesse was industrious and never did anything by halves. He wrote songs and skated and cooked and sewed and took photos and developed them and knew a lot about everything he was interested in which was a lot of things. He made funny short films and rented the town theatre and enlisted the talents of his friends and put on variety shows and he did this in every town we lived in afterward too, with increasing success over time. After he moved into my house he got to work right away planting a garden and was careful and diligent about it and it was huge and abundant. He had become interested in peppers for some reason, maybe because I often waxed poetic about the time I had lived in Taos and grown chiles on my rooftop. He prepped the garden and got to work finding seeds, then planted twenty-four different varieties of peppers—spicy peppers, sweet peppers, Hungarian wax peppers, banana peppers, ancho, serrano, pueblo, poblano, Anaheim, cayenne, bell, Calabrian, habanero, jalapeño, guajillo. When they were harvested he made a big goulash out of all of them, served over rice. It was good and he shared it and after about an hour everyone who had had some was doubled over or rolling on the floor in misery. We had to take turns using the toilet—crawling back and forth from the bathroom on our hands and knees. We never worked out exactly why the goulash got us like that but figured it had something to do with the twenty-four different kinds of peppers.

Everybody who lived at the house and most of the people who visited were always or a lot of the time at least a little fucked up, buzzed mostly or high on weed, and everybody was a floundering kid just out of high school or a floater or dweller or wastrel of some kind or a skater or artist or musician and often a combination of a few of these things but even so a lot of us had jobs or some degree of responsibility and, depending on what your criteria was, most of us were, somewhere deep down, fairly upright citizens.

There were some hippy kids who had used to live on the property but didn’t anymore but still grew weed there in big pots and I was totally unable to get them to move the pots somewhere else because every time I said something about it they countered with ‘it’s all good, Sister, just live and let live!” until the day I said I’m not your sister and I don’t want to get busted because you grow weed on my property …and then things became a little strained. In the end they moved their pot pots just off the property line but still within view of the house and I tried to let that be good enough, it was good enough, probably, but I had a hard time letting it be. The hippies could be pushy like that; one time Jesse’s car broke down and Sage—a white guy with dreads—ran over, pulled a huge crystal off from around his neck, said “it has healing energies, man,” and put it on the hood over the engine. We all stood around for a while waiting for the car to start but it never did.

The first time Jesse ever came over to the house I was smoking weed and listening to records while painting my kitchen various shades of yellow, probably because that’s what my mom had done when I was little. She had painted the kitchen and a couple of other rooms multiple shades of yellow, as well as green and purple and blue and bright orange and red. I had been embarrassed when friends came over, because of that and because we lived in a big dilapidated house and the other kids had bigger, nicer houses and moms who hired other people to paint them and when they did it was always white. But then my dad’s book about a horse trainer got optioned for a movie and my parents came into an unlooked-for eleven-thousand dollars and my mom switched gears. Suddenly there was a new Camry instead of the old Bug and the kitchen got painted white, except for the cupboards which stayed yellow for a bit longer, but when the movie came out those got painted too. The whole house began to look respectable but by then it was too late; I had started to sneer at convention and wondered why my parents weren’t cool anymore.

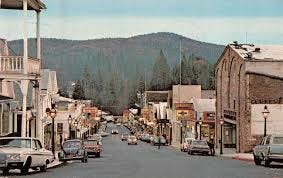

My room was at the top of the house and had big windows overlooking the canyon. There was a skylight and lots of stars to look at as I fell asleep. I didn’t have a job when I first moved in but I still kept to a kind of schedule; first thing every morning I’d wake up, smoke some pot and put on a record. I listened to the same records in the same order every day, not because I’d planned it that way—it was just a sort of musical progression where one thing led to another—kind of like the way a DJ might get the crowd more and more pumped, bit by bit, one record at a time. I would start with one song on my *Yugoslavian folk music record—a stark and dissonant chant—then I’d switch to my Italian folk music record, which had lots of waltzes and tarantellas, guitars and mandolins. I’d replay the instrumental on side two a few times because it had a mandolin solo that was more or less just a scale but a scale can be everything if it goes in the right direction in the right key and this one reminded me a lot of Ernest Ranglin’s guitar riff at the end of the song Old Rocking Chair by the Skatalites, so then I’d put that on, and it was ska so it always put me in mind of the Specials, which were also ska but also a bit punk which was nice because by then I was awake and ready for something with more energy. So I’d listen to the Specials and then I’d smoke a little more pot and put on Johnny Cash which always felt perfect—a happy medium, somewhere in the middle, energy-wise. I’d listen to Don’t Take Your Guns to Town a few times and by this time I was pretty lit and the song made me feel a bit jaunty, the rhythm had a rollicking swagger and I could picture a cowboy, walking to town—hopefully without any guns, but definitely with an attitude, a thumb hooked into his belt loop—and it put me in mind of walking to town myself, and by that time usually my friend Jun was up, or showed up because I actually never knew where he lived, maybe in another closet? Anyhow he’d appear, always smiling and a little drunk. If he wasn’t drunk he was probably stoned, and always smiling, and he had the worlds nicest smile and never treated me like anything other than who I was—a weirdo who loved listening to records—but certainly not in a romantic way and if he ever felt like that I never knew it. Wogart, who had impeccable taste, was crazy about Jun and vice versa and after they had taken time to greet each other the three of us would make our way down the gravel road that ran alongside the creek, past the acreage that nobody could sell because it was in the flood zone—although it seemed like there was always some shady realtor trying—and if one was there with a client when we walked by we’d wait until we were out of sight, but not out of ear shot, and shout “IT’S IN THE FLOOD ZONE!” then continue on, past the clearing under the trees that the kids called Hobbitland, and on across the bridge over Deer Creek into town, turning left on Pine street where Jesse had a job cooking in the open kitchen at the South Pine cafe. Wogart went up the alley to the side door of the restaurant where he sat patiently on the steps, waiting for scraps, and Jun and I went in the front door and sat down at a table. I looked at the specials board which said “Special: Garlic and Onion Omelette,” and it sounded simple but good so I ordered it and talked to Jun and tried not to look at Jesse too much but when my omelette came it didn’t have garlic or onions, it was just eggs, and I looked over at Jesse and noticed his half-closed eyes and big grin and realized that he was blitzed, bombed, baked out of his skull and I laughed because he was so gone he couldn’t even put the two ingredients in the two ingredient special that he’d come up with himself. I also regretted my plain egg omelette and wished I could ask for my money back but it was on the house which is what happens when you’re sleeping with the chef. After Jesse got off work we went across the street to Wally’s mini-mart and bought a six pack or a couple of six packs and got in his car and drove up to the river.

I had never really drunk before then—I only started to once I met Jesse. He was great and he drank so I drank, a little at first and then a little more and then the flood kind of loosed and drinking became one of my favorite things to do. We smoked pot too but mostly we drank. Sometimes we did other things like mushrooms which I liked to cook in an Alfredo sauce and serve over pasta. My friends laughed at me and asked why I couldn’t just eat the mushrooms plain like everyone else, you’ll feel sick to your stomach anyway after they hit, they said, so what’s the point, but I was a food snob who had, as a kid, cut the description out of the back of a cardboard package of Stouffer’s Fettuccine Alfredo and pasted it on the wall next to my bed where I could read it often. It said “fresh egg noodles, cooked in a sauce rich with cream, butter and aged parmesan, lightly seasoned with cracked black pepper,” and I liked the way the blurb both described the food, which I loved, and was full of consonants that got stuck on my tongue. In high school I recited it to my friends and they caught my enthusiasm so we decided to start a Fettuccini Alfredo club or gang which involved cooking it every Friday night while watching movies at each other’s houses, and hiding behind cars in supermarket parking lots, then jumping out at passerby and yelling, “FETTUCCINE …ALFREDO!”

After a summer spent fucking off and going to the river I got a job cooking pizza at Cowboy Pizza which was around the corner from the South Pine cafe. I liked working there because the owner played lots of old cowboy music like Roger Miller and Tex Ritter and Webb Pierce who had a great song about a glass called There Stands the Glass. I took the job pretty seriously and worked hard. I was intent on making good pizza. I’d heard about New Haven pizza which many consider to be the gold standard of great pizza and even though I’d never had it myself I knew that New Haven pizza was famous for having a charred crust. A thin charred crust. I tried letting the crust at Cowboy Pizza which was not thin get black sometimes but the customers always returned it saying it was “burnt” and I shook my head at their ignorance. My boss asked me to please stop burning the pizza. Eventually I got good at it though and some of my recipes were featured in the Nevada City Senior Gazette.

I worked at the pizza place but still had to collect rent from my tenants—who were also my friends—and it was hard to do and made me feel like a dirty capitalist and also super uncool so to offset these feelings and try to make good I would sometimes let one or another of them come into Cowboy Pizza before opening and I’d make them a personal pizza and give them a fancy beer from the fridge and I did this and felt better about things until the owner came in early one day and caught me and told me I was losing money for the restaurant this way and then I felt guilty and paid her for the difference and nobody in their right mind would ever have dreamed I’d become a business owner myself someday—me and Jesse—but that’s the kind of shit people do when they grow up I guess and we did.

*Yugoslavian record on the turntable.

“Old Rocking Chair” —a touching song. I think the guitar riff at the end is the best thing I’ve ever heard, every time I hear it.

Next Chapter: Part 8

Am I right in detecting a kind of different, stream of consciousness, prose style in this piece vs your other ones? I like it. Full of interesting details. Like "Italian folk music": what was that? And of course fettuccine Alfredo, the one dish that's more popular outside of Italy than it is here. Hilarious. :)

Fettuccine Alfredo. How a simple substory in a bigger one can make me smile. This was a truly lovely read.