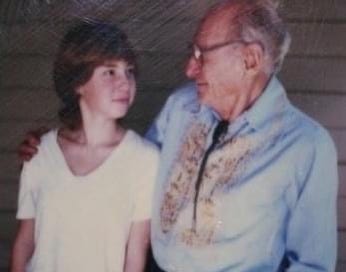

As a kid, I'd sometimes go with my dad to visit his parents in Los Angeles. Their house was big, modern; not ostentatious, but elegant. And quiet. There were thick carpets and oriental rugs everywhere, which added to the hushed feeling. Not like our house—a dilapidated Victorian with creaky wood floors, always full of people, music, noise. My grandparents were quiet, and there was a sense of intellectual and moral goodness too, which, although good things in themselves, was oppressive to a kid who would have been more comfortable with less of it—to take the pressure off. The idea of anyone behaving badly or even loudly in such a setting was unthinkable. But my grandfather, Hermann, had a sense of humor, although it took me some time to realize it, and he was generous and kind. He was more thoughtful than anybody I've met since, except maybe my father and my husband and ex-husband. Probably he helped set me up for something good in that way, in the way of husbands I mean, formed my taste a little, by his example.

My grandparents had a kind of helper—a young woman named Lucy. Lucy had emigrated from Mexico and couldn't speak much English when she first got to L.A. My grandfather paid for her to go to college and learn. He drove her there himself. Later, he taught her to drive. Lucy stayed working for him, helping to take care of my grandmother Vita, living there part time—even after she got married—for nearly forty years. She took care of them both, really.

When we visited, Lucy would make lunch for us all, while my father and grandfather spoke together quietly nearby, helping her occasionally as she directed them.

“Hermann!” she would say. “Here, this is for you, you like the peaches very much, don't you? Will you please set these on the table.” And, with a big smile, she'd put a few canned peaches on a plate and hand it to him. Hers was the only loud voice in the house, a little jarring, but pleasant, and you could tell she was adored, the boss.

“Thank you, dear,” my grandfather would say, as he carried the dish to the table.

“Vita would probably be glad of your company,” he'd say to me. “She's in the den watching TV. Would you like to go in and join her until lunch is ready?”

I looked over at my father, who gave me a small smile, then at the ground. I didn't want to go in.

“Here you are!” said Lucy, taking over. “You take these, a little snack, and go see your grandmother.” She handed me a plate of rice cakes.

“Come. I'll go with you.”

I followed her down the hall and waited behind her while she opened the door.

“Vita, dear, here is your granddaughter Anna to spend some time with you, isn't that nice?” She said loudly. My grandmother, sitting in front of the TV, looked up.

“Very nice, dear,” she mumbled.

I went in then, and Lucy shut the door behind me.

My grandmother sat in her wheelchair, head lolling against her chest. I sat down on the carpet nearby. The TV was on. For a moment it seemed like she was aware of me, but then her head began to nod, and her eyes closed. I sat still. After a little while she opened one of her eyes and looked at me. The other was heavy, half closed, unseeing.

“You are a Kavinoky,” she said.

“No. I'm a Schott.”

“You have the Kavinoky red hair. My father and my grandfather were Kavinokys. Then I married Hermann.”

“I'm Max's daughter,” I said, falteringly. “Your son Max …I'm your granddaughter.”

“My son,” she repeated. “Maxie.”

“Yes,” I said. “I'm his daughter, Anna.”

She sat there a while, nodding, then looked at me gently with her one open eye. She smiled a little, but seemed not to remember our conversation from a moment before.

“You are a Kavinoky,” she said again, “you have the Kavinoky red hair, the red hair of the Kavinokys. I remember all the Kavinokys.”

She talked like that for a little while, saying the names of people long dead, until her head started to nod again, and finally rested, drooping against her chest. Her eyes had closed. A great stream of drool rolled down her dress. I sat still and watched, until they called me to lunch.

Lunch was but a bleak repast—my grandfather was on a special, heart-healthy diet after having had a triple bypass. There were a few carrots, some cottage cheese, rye crackers, and tinned peaches. That was it. It was pretty dismal, to my thinking, but the diet was a reputable one, and it worked—he stayed on it for the rest of his life, which was long, and never had any more problems with his heart.

My grandmother was first diagnosed when my father was five. She had a non-malignant brain tumor, which couldn't be completely removed because it would damage the surrounding brain tissue. At first, after the operation, she got better, as the doctors had predicted she would, but they'd also predicted that, as the tumor grew, she would gradually get worse. As it turned out, they were right. For most of my fathers life she was incapacitated, wheelchair bound, paralyzed on her right side, with little or sporadic brain function.

Before that, she'd been a schoolteacher, and, as I learned from reading her teenage diary—a clever, funny young person.

When I was in college my grandfather called to tell me that she had died. I tried to say what I could to console him. “That's alright dear, thank you,” he said. “She died in her sleep. It was very peaceful,” he added, reassuring me, instead.

I never thought to try and console my dad though. I guess because I simply didn't think of her as his mother.

When my grandfather was very old, and dying, he gave me the diary that Vita had kept when she was seventeen. I took it home and read it.

“Hermann Schott is coming over tonight to help me study,” she'd written. “He sure is keen. But I'm just looking forward to the after-math.”

I didn't like the food at my grandfather's house, but later in life I became interested in eating for health, myself. I learned about nutrition and tried to help the people I cared about to eat better. It was never much use, but I tried anyhow, much to everyone's irritation.

When I was in my late twenties, I went back to my home town for a visit. I remember standing around in my parents kitchen one night talking to my dad, who was frying a hamburger on the stove. I started lecturing him about nutrition. I talked about heart disease, and reminded him of his father. I became energetic on the subject. As a long time vegetarian, I may have taken the moral high ground.

My dad stood there, frying his hamburger, listening. He let me talk, nodding occasionally, quiet.

But after a while he'd had enough.

“Just a minute,” he said, smiling. I stopped talking and waited.

“I would like to say something now.”

There was a twinkle in his eye that I didn’t quite like.

“Um. Okay. What?”

“I'll tell you one thing,” he said. “You may think you know what you're talking about, and maybe you do, but I'll tell you one thing–”

“You just said that! What?”

“While I appreciate your concern, I'll just say this–”

He turned to me and grinned.

“If I can't eat another steak,” he said, “I'd rather croak.”

And then he laughed.

The next morning my dad went to the doctor for a routine exam. But they heard something weird with his heart. They ended up giving him a treadmill test, and an ECG, and the upshot of it was that he got sent home with a bottle of nitroglycerin (to keep on him at all times) and an order to "take it easy" until the following morning, when they had scheduled him for an emergency quadruple bypass.

We stood around the kitchen again that night, talking, trying to digest the news. Like the rest of us, I was terrified. I remembered the night before, when, in our innocence, unaware of the impending danger, we had argued about nutrition. It seemed like too good an opportunity to pass up.

“Dad,” I said, “I don't mean to take advantage, but, in light of our conversation last night? I can only say ...I told you so!”

“I guess you did,” he said.

And then he laughed.

My dad survived his operation, although for better or worse he never changed his eating habits afterward. I asked him why he couldn't just do like his father had, and start eating a heart-healthy diet. I wondered that he hadn't been scared into it. I asked him why he was still eating big, buttered scones every morning, without a care in the world, or, at least, a thought of his health.

“Man,” he said, grinning. “I tell you what.”

“What?”

“As always, I appreciate your concern, but the way I see it…”

He paused.

“Yes?”

“The way I see it is very, very sensible. I figure that it must have taken me about thirty years to build up all that plaque in my arteries, but now they've cleaned it out, so I have another thirty years to build it back up again. Would you like a scone? They're mighty good!”

Loved it, Anna. Your prose paints these vivid scenes that scroll one after the other delicately, almost imperceptibly. With your thoughts in-between. Like this: "I never thought to try and console my dad though. I guess because I simply didn't think of her as his mother."

Schott, hello 💐

Your writing. Just. Lovely.

You have beautiful gentle vibrations oozing out, reverberating to enchant.

I, personally, would like to save all your writing and print it all out, file it in a large A4 lever arch file....savour your reminiscing, all my rest of my life. You twang me so.

It's like a composite of sooo many writers, I've had the good fortune to read, over my life....

Thank you, Schott, you are a wonderful Earthling. 🙏🏻🧘🏻♀️🌌

(ps: I can identify, with your pa...me too, cardiac misbehaviour.

on trinitroglycerine or I think, it's called glyceral trinitrate...same diff, what the heck...I'm too much of a chicken (me being a vegetarian🙄) for the advised bypass...so far so good, six years after my doc hit the ball to my court.)

You take care.

Love to you and family 🙏🏻🫂🫂🫂🫂🫂💙🌛🌠🧘🏻♀️🌌